Tom Konrad Ph.D. CFA

Much fuss has been made about green jobs. Do they exist, and are more “brown” jobs displaced for every green one? Given all the political rhetoric, it’s not surprising that there is also considerable confusion about green jobs.

There should not be. While pinpointing the actual number of jobs created or destroyed by any particular policy will always be fraught, the underlying microeconomics are rather simple, and understanding those microeconomics can make it clear if a given policy will be a net creator or destroyer of jobs.

While there are many considerations that should be taken into account when forming policy, such as encouraging new technology which may allow future growth, and improving the health and well-being of citizens, I am going to restrict myself to the goal of promoting job creation and economic activity in this article in order to keep the discussion relatively simple.

My conclusions should not be considered in a vacuum. Many considerations, not just jobs, should be considered when forming policy.

(Picture reprinted with permission from UCS / John Klossner)

Re-framing the Question

In order to avoid the rather pointless debate about the definition of a “green job” I will re-frame the question to one that I believe both sides would agree is more important (at least if they were able to put aside partisan bickering):

Does a particular green policy create more jobs than it destroys?

If a policy is both green (which I define as lowering our use of resources and/or environmental impact) and is a net creator of jobs, all parties should agree that it is a good policy. Green policies which destroy jobs, on the other hand will require further analysis as to whether the environmental and health benefits outweigh the economic losses, a question which requires putting relative value on various benefits, and cannot be resolved purely by economic reasoning.

Which Policies are Net Job Creators?

I’m aware of two mechanisms by which a policy can increase or decrease economic activity and hence number of jobs.

- Jobs can be created or destroyed by substituting labor for capital, energy, and/or other resources in production.

- If a policy increases economic efficiency, it will increase economic activity and create jobs. If it decreases economic efficiency, it will reduce economic activity and destroy jobs.

Substituting Labor for Energy or Capital

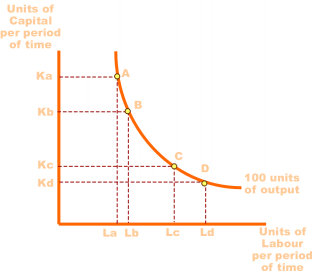

Image Source: Wikipedia

A basic tenet of microeconomics says that there is a tradeoff between capital, labor and natural resources such as energy in the production function. In particular, you can substitute capital for labor (by mechanization) or labor for capital (by using shovels and picks instead of bulldozers.) Now add energy into the mix, and you can substitute fossil energy for either capital or labor to attain the same production.

For example, a hybrid vehicle substitutes capital and resources (in the form of an electric motor and batteries) for energy (less fuel consumed to do the same work.) A bus substitutes labor (the bus driver) for capital, resources and energy (lots of cars and fuel consumed.) A green building substitutes labor (better architecture/construction) and some resources (extra insulation) for energy.

From this perspective, any policy that promotes the substitution of labor for energy will create green jobs, since you get more work and less energy consumed. Shifting people out of their cars and onto mass transit will create jobs because there will have to be drivers and people managing the transit system, where before no one was paid to drive. To the extent that the transit system can be paid for out of the reduced fuel costs and car ownership costs of the former drivers turned riders, the number of jobs created will be a pure economic gain.

Multiplier Effects

That brings us to the other major potential source of jobs from green policies: economic multiplier effects.

To the extent that green policies improve economic efficiency by overcoming economic barriers to cost effective green solutions, these policies will result in greater economic activity, and hence more jobs. The strongest critique of “green jobs” initiatives is that they simply shift economic activity from out-of-favor “brown” sectors to more politically correct green ones. Yet when a policy improves economic efficiency, it does not just shift jobs and capital around in the economy: it creates economic activity and jobs.

Not all green policies improve economic efficiency. For example, subsidies for not-yet-economic types of renewable energy such as wave power and solar installations may be justifiable on the grounds that they are helping to promote needed future technologies, but they probably come at a net cost to near-term jobs (even if they may create more jobs in the long term by allowing the creation of new types of businesses.)

On the other hand, policies to promote energy efficiency will be strong net creators of jobs, because the cost of energy efficiency is typically only a fraction of the cost of the energy saved. The very existence of opportunities to save significantly on energy bills at modest cost is proof that the energy market is inefficient. In an efficient market, all such opportunities would have already been taken.

After the energy efficiency measure has been installed, the cost savings can be used for useful economic activity, rather than wasted on unneeded fuel. This money will then spur additional activity and stimulate jobs.

Using Fossil Resources to Stimulate Growth is Like Stimulating Growth With Debt

Short term jobs (green or otherwise) should not be the only consideration when forming policy. A short term focus on jobs today can end up doing long term economic harm. For instance, if we spend too much borrowed money to create jobs today, the long term drag on the economy caused by paying back the debt will leave everyone worse off.

Economic growth fueled by the extraction of non-renewable resources is very similar to economic growth fueled by debt. When we extract these resources and use them, we increase economic activity today, but their non-renewable nature means that we lose the opportunity to extract and use them tomorrow. Hence, the economic stimulus today comes at the cost of an economic drag tomorrow, and the future economic drag will generally be larger than today’s stimulus, since improving technology should allow us to get more benefit from each unit of resource in the future.

Using renewable resources to stimulate growth does not have this problem: Tapping the wind or the sun for energy today does nothing to diminish the wind or sun tomorrow. Hence, to the extent a green job relies on renewable resources and a brown job

relies on fossil resources, the green job should be preferred, even before taking the environmental benefits into account.

Policy Implications

If we only consider job creation, the focus on policy should be on creating jobs and economic activity, with a preference for green jobs, since those impose less of a cost on future economic activity than jobs based on extractive industries.

Green jobs can be created either by substituting labor for energy and capital, or by reducing energy waste so that the money previously wasted on energy can be put to more productive uses. For policy makers who wish to create green jobs, the implications are clear.

Green job programs should focus on two types of opportunities:

- Industries where labor can usefully be substituted for energy or capital, such as mass transit.

- Breaking down the barriers to energy efficiency which can stimulate economic activity by allowing money that would otherwise have been wasted.

The converse is also true: if the goal is to create jobs and stimulate economic activity, subsidies and other policies which encourage the substitution of capital and energy for labor should be ended, especially those subsidies which encourage the extraction of non-renewable resources which only create jobs today at the cost of future jobs.

The most cost effective policies for creating jobs will be those that break down the barriers to the adoption of cost-effective green technologies, especially energy efficiency. Ironically, most energy subsidies have gone into capital intensive sectors such as nuclear and extractive sectors such as oil and gas.

A very cost effective way to produce jobs would then simply be to remove subsidies from fossil fuels and nuclear energy and redirect them towards the most cost effective clean technologies.

Increased support for and promotion of public transit could do much more to reduce our dependence on imported oil than support for domestic drilling (which will only make us more dependent on imported oil in the future by using up domestic resources sooner) while also creating jobs.

Meanwhile, energy efficiency programs such as cash for caulkers can cost-effectively reduce energy bills and free up money for other sorts of consumption while also creating jobs in the depressed housing sector.

There is a lot of confused discussion about green jobs, so thanks for tackling this topic.

I’d put it a bit differently: on the micro-economic level, if clean energy is more labor intense than conventional sources, then employment should rise. If clean energy is more efficient and reduces costs for energy consumers, this should increase GNP, but there is also rebound effect on energy sector, it would be smaller (in terms of inputs).

Two big questions are:

1. is the economy already at full employment? if so, clear that new jobs cannot be created. If not, then have to look at macro-economic impacts of clean energy – multiplier effects, etc. And the fact that the US (or other countries) are part of global economy, so efficient clean energy might improve competitiveness of other sectors. But international clean energy product and investment flows make picture very complex.

Thanks David,

You put it much more clearly than I did. I also appreciate you bringing in the question of the level of employment. (Not that we have to worry about full employment just now, but it’s an important long term consideration.)

I’m not sure if I agree with you on the rebound effect, though. If we increase consumption of energy in response to the lower cost of energy, we will be doing it because we gain some net utility from the increased use of energy. That gain in utility should come with an economic increase, and hence also create jobs.